- Home

- Padma Lakshmi

Love, Loss, and What We Ate Page 8

Love, Loss, and What We Ate Read online

Page 8

While part of my overindulgence came from my lack of experience, the rest came from self-doubt. I’ve always been intent on proving that I wasn’t just a five-foot-niner plucked at random from the catwalk. I had, or at least I thought I had, some credibility. I’d written two cookbooks and had hosted food documentaries and a cooking show on the Food Network. But still I worried. I had more than a touch of imposter syndrome. Tom had proven his chops cooking for great chefs and heading up more than a couple of restaurants that were well respected in New York. Gail had gone to culinary school and worked as an assistant to Daniel Boulud and to Jeffrey Steingarten before joining Food & Wine magazine. Our show was the sister show to Project Runway, and it made sense that a model hosted a show on fashion. But I didn’t want people to think that Bravo had just put another model into the same format for their new food competition show.

I got looks at first from a few of the guest judges who didn’t know me at all—most of them accomplished chefs—that virtually screamed, “Why the hell are you here?” I felt they thought I was nothing more than a pretty face. And ever since my first cookbook came out, I’d heard the tired complaint: What does a model know about eating? So as soon as the food came out, I ate like I had something to prove. I ate to the point of discomfort. Sure, I hadn’t broken down a side of beef or cooked on the line. But I’d eaten and learned about good food all over the world—the finest bastillas in Marrakesh, tons of meals in Paris bistros, fresh pasta made by expert hands in Milan, the best biryani in Hyderabad, and the most exhilarating chaat in Delhi.

My love for food was born in India, where I spent the first four years of my life and many summers afterward. The vivid flavors I experienced there will forever be the standard to which I hold any food I eat today. Perhaps my most formative food experiences happened when my mother sent me back to Madras to study for the year. It was also during this time that my mother was divorced by my stepfather V., because he did not believe what she and I had told him about what happened to me in my bed.

When I arrived in Madras I immediately entered third grade (or “standard,” as it’s known there) at St. Michael’s Academy, the new local Catholic school, in the middle of the school year. It was an English medium school but students were required to study a second Indian language from kindergarten on. I spoke Tamil more or less as well as my peers, but because I’d left India at age four, I couldn’t read or write it. However, I would have been behind my classmates regardless, because the Indian elementary school system is far ahead of the American. Worst of all, I would have no summer break and I would be the new girl yet again.

Moving between India and the States brought changes that left me perpetually confused and feeling like an outsider. For one, I couldn’t keep my spellings straight—in the U.S. I’d write “colour” and “flavour,” and in India, “color” and “flavor.” Then there were more embarrassing cultural mix-ups. In the U.S., wearing a tank top to deal with heat was perfectly normal, but the same outfit in India came off as wildly provocative, drawing snickers from my cousins and tut-tuts from my uncles. Deeper than that, I was always missing some important event of pop culture or rite of passage that my peers had experienced, because I was in the wrong country. I didn’t wholly identify with the collective experiences of children in either place. I had one foot in each culture, but no firm footing in either of them.

At the time, the school consisted of just a few square rooms topped with thatched roofs, standing in a dusty courtyard surrounded by neem trees. It was in the Adyar neighborhood, near the Aavin Milk Bar, a major landmark in seventies Madras, where so many families took their kids for shakes or sticks of frozen milk. Located at the intersection of five roads, the Milk Bar was a round compound and was shaded by trees, providing lovers a safe place to furtively meet camouflaged by swarms of friends. It was also a place where young families could enjoy an inexpensive outing in the cool evening air. We always passed it on the way home from school and looked longingly at it like some sweet oasis.

Around 3:45 p.m. every weekday afternoon, the St. Michael’s school bus spit me out, along with my cousin Rajni, below our little flat, always teeming with activity. In one room lived Rajni and her parents: my mother’s younger brother Vichu and his wife, my aunt Bhanu. Once when I was three I tried to kill Rajni by stepping on her. Soon to arrive on the scene was her brother, Rohit, my main rival for my grandfather’s affection. In the second bedroom were my two grandparents, me, and Neela, my mother’s youngest sibling. As if that weren’t enough, my cousin Aarti, my uncle Ravi’s daughter, often came from Delhi to stay with us, too, as did Neela’s cousin Vidya, the daughter of one of my grandmother’s brothers. Add to that my grandfather’s students, who, hoping to raise their exam scores, would loiter in the living room hall on Sundays. Needless to say, the time spent in my grandfather’s flat stood in stark contrast to my life as a latchkey kid in the crowded metropolis of New York City.

Rajni and I arrived at a rare time of quiet in an otherwise bustling home. My grandparents were usually napping in their room. Once we washed our hands and feet and had a snack, we were encouraged to nap, too, at least until the sun sank and the temperature dipped. Whether we napped or not, we weren’t allowed to go out in the sun until after 4:30 p.m. My grandmother thought we were already too dark from playing sports outside during school. You had only to read the matrimonial columns to see that light-skinned girls had it easier, even in a brown country like India. Indian culture was rife with color prejudice. Often the first word on the listing boasting of the eligible boy or girl for marriage would be “fair.” “Wheatish” was used when they couldn’t get away with saying “fair,” and no one wanted to be called the euphemistic “dusky.” Our time playing outside during those summers was brief. We had only a couple of hours after 5:00 p.m. tiffin—the subcontinent’s version of its colonizers’ “tea,” which brought dosa and kachori rather than cucumber sandwiches—to play fox hunt or a violent game of tag. Sometimes we’d build sand temples adorned with red and white hibiscus flowers, before darkness when the mosquitoes became too menacing.

The nights were so hot that most adults congregated on their verandas, keeping an eye on us as we played. The sounds of our neighbors’ lives blared through the neighborhood or colony almost as loudly as the TVs (which we ourselves only acquired in 1977). From our spots in the sand, we’d occasionally hear laughter or crying or the crack of an open hand connecting with soft flesh. Corporal punishment was the disciplinary tool of preference. I don’t ever remember being grounded or having a privilege taken away. I had none to confiscate.

At times, we kids in the colony all seemed to function as a large, unofficial family. Often we would stop playing to find the closest door and bang on it, begging for water, until someone answered. With a sigh, some unlucky woman would bring out a pitcher and tumbler, which no doubt emptied out her small fridge’s supply for the night, and watch as we all took greedy gulps. In a drought-ridden country like India, it was very bad form to refuse anyone water, and we children knew this. So those who lived on the ground floors of the apartment complexes often became de facto water coolers.

The close proximity in which people lived in India was in stark contrast to my independent existence in America. Here, everyone knew one another’s business, and in general personal space and privacy were ephemeral. For naps, I always chose a spot on the cool green marble floor close to the side of the bed where my grandfather, or KCK as he was called, slept. It was that same spot my grandmother favored in rare moments of quiet. I watched his large, bearlike belly, barely covered by his undershirt, rise and fall. You could time a clock to the sound of his gentle snoring. I’d often wait for the sounds of his waking: the familiar clearing of his throat, a grumble, and a mumble. He’d open one eye, peer down at me, and whisper, so as not to rouse my grandmother, a notoriously light sleeper, still asleep beside him. “Psst, eh, Pads?” he’d say. “There’s a two-rupee note in my bush shirt pocket hanging there. What say you go to All-In-

One and grab a little something for you and me?”

The All-In-One was the first store to sprout up among the colony flats, the Indian version of the many bodegas and Korean delis that define daily life in New York. The All-In-One was the size of a small single-car garage. It sold shaving cream, laundry detergent, plastic wastepaper baskets and buckets for bathing, the disinfectant Dettol, bandages, medicines from Valium to aspirin to asthma inhalers, scissors, paper, pencils, copybooks, savory snacks, chocolates, and Rasna, a powdered drink mix similar to Tang—most of it kept under a glass counter or behind it in a glass cabinet. There were little jars of candies and biscuits and five-paise (about one-twentieth of a rupee) packs of Chiclets. There were two coolers, one for soft-drink bottles and the other, a metal icebox, for Popsicles and ice cream. In the back of the All-In-One, jute sacks of rice, sugar, lentils, coffee, and other raw goods lay heaped behind an iron scale. Two round iron plates hung from the ceiling by chains attached to a bar. The clanging sound the plates made as goods were measured and sold was ear-piercing in intensity. I made anywhere from three to eight trips a day to the All-In-One. I could be dispatched there for oil by my grandmother or for a notebook by Neela, or accompany my uncle Ravi when he was in town and went to buy cigarettes on the sly, bribing me with cold Indian sodas or Cadbury Dairy Milk chocolate bars.

My postnap trips to the store were always clandestine. After instructing me to fish out the rupee notes from his shirt pocket, my grandfather would put a finger to his lips. I knew I had to remove his shirt from the hook by the cupboard without jingling any change that may have been resting in its pockets. I had to take the amount he instructed and slip out of the room. Even if I’d succeeded in not waking my grandmother, I still had to elude inquiries from my busybody aunt Bhanu, who, if not napping in her own room with her daughter, Rajni, would be in the kitchen preparing for five o’clock tea and tiffin.

I never bothered to fish out my chapals (slippers) from the shoe closet by the front door, because the sliding wooden doors made too much noise. And anyway, our whole street was sand. The rest of the neighborhood kids and I played barefoot. But the main road was tarred. At that time of day, with the sun high in the sky and my path baking under the Coromandel heat, walking briskly, let alone casually strolling, would mean second-degree burns. But if I ran as fast as I could, literally hotfooting it, I could just about endure until I reached the cool relief of the All-In-One’s stone floor to complete my task. I was to buy two single-serving vanilla ice cream cups, one for me and one for KCK.

He loved those little cups, each with a wooden spoon taped to the bottom. I usually had enough change to buy myself a small packet of rose mints, Pez-shaped baby-pink candies with a mild but distinct flavor and light floral scent. On the way home I carried the two cups in one hand and the mints and change in the other. I tried to run even faster, because in addition to suffering the scalding tarred road and maintaining the secret of my mission, I had to contend with the melting ice cream. KCK and I ate the cups of ice cream quietly in the bedroom while my grandma slept, beaming at each other between bites, the lovely pain of cold in our mouths.

When I went out for my mission, I always left the front door slightly ajar, barely noticeable to the passing eye, so I could easily sneak back in. It almost always worked. Once, though, Aunt Bhanu caught me upon my return as the door squeaked open. “Eh?! What were you doing outside in the sun?” She seemed really mad, as if I’d stolen from her purse. Just then my grandfather cleared his throat loudly and called out for her to bring him tea.

“Pads just came in from somewhere, Tha-Tha!” she tattled. “She’s left the door open and gone without telling anyone. Now she has something in her hands and all!”

“It’s fine, Bhanu, I asked her to fetch me a stamp from All-In-One.” Perhaps the only thing All-In-One did not sell was stamps. “I told her to get a little something for herself. Send her here, I’ll deal with the child. And bring me my chai please, my throat is bothering.”

Bhanu knew my grandfather was never short of stamps, given his weekly trips to the post office for his pension checks, but she also knew never to cross her father-in-law. I slid sheepishly past her and into the bedroom. The commotion of course had roused my grandmother, lying in the bed. As soon as we put wooden spoon to paper cup, she said, without moving or even opening her eyes, “Will you please stop putting that child up to no good!”

Rajima kept a low profile and rarely contradicted her husband outside of the bedroom. But in the privacy of that room, from our place on the floor, Neela and I heard her speak her mind. We learned who really held the seat of power in our family.

I wouldn’t understand until years later why my errand caused such a row between two loving and mild-mannered people. KCK was diabetic. Severely so. And he was afflicted with a mighty sweet tooth. He’d need one to love the vast array of saccharine Indian sweets, which he did but which I decidedly do not. He adored ladoos and jalebis and payasams laced with cardamom and cashews in thick, sweet milk. Payasams I didn’t mind, but only as an adult have I come to like ladoos, tiny balls of deep-fried chickpea-flour batter mixed with nuts and raisins and bound by syrup into large balls. I still feel sick after eating the traffic-cone-orange jalebis, sugary dough extruded into hot, saffron-spiked oil.

Fortunately for me, he didn’t stop at these traditional confections. He also kept a sleeve of Marie biscuits hidden behind the volumes on his bookshelf. He’d snack on them, I’m sure, but he’d also dole them out as treats for us kids. Occasionally, when a burst of affection for us overtook him or when one of his students did well on a quiz, he’d produce a biscuit, as if out of nowhere, as a reward.

KCK taught me to make the first dessert I ever even considered replicating myself: a simple cold payasam of mashed bananas, milk, sugar, and cinnamon or cardamom. I have always preferred salty, tangy, crunchy things to sweets, especially the aggressively sugary Indian sweets, but for him I would have eaten all the ladoos and jalebis in Madras. My grandmother allowed me to make banana payasam for the prasadam that accompanied the religious ceremonies we marked at home.

The flavors I loved most were the tart, sour notes in things like green mango and tamarind. Before school, my new best friends—P., K., and C.—and I would sit under a tamarind tree on the campus of St. Michael’s Academy. From its shade, we’d watch Mrs. Balagopal, my plump, smiling third-grade teacher, arrive on her scooter, her colorful, wildly printed sari fluttering behind her like a superhero’s cape. I’d look for D., a boy who lived in my neighborhood. He was taller than the others and a great cricket player to boot.

Every so often, as a strong breeze shook the boughs of the tamarind trees, we’d hear a rustling and pods would tumble through the lacy leaves and fall to the ground. Sometimes they would hit us as they fell. When they’re brown and ripe, the papery pods contain sweet, tangy flesh clinging to stone-like seeds, but as kids we’d also eat them when they were still green. My grandmother loved these young pods, still seedless, crisp and tart like green mango. “Kanna, there are some nice imli pods at your school,” she’d remind me. “Knock a few down and bring them back in your school bag.” If none fell on their own, I’d chuck stones at the tree.

The silky rustling of tamarind leaves always reminded me of the rustling of my grandmother’s sari. Women in my family keep their bodies hidden, their breasts and bellies concealed even from their children and husbands. Only after my grandmother had cleaned up with Bhanu, turned off the lights, and put everyone to sleep would she dare creep through the bedroom, past me and Neela, to change her sari. I’d hear her unwrapping herself from six yards of fabric, the colorful silk and the folds of her body invisible in the darkness. I’d hear her searching her sari for the rupees that she kept tied in a small bundle of fabric at the end, a sort of makeshift pocket. Indian women hide many things in their saris: keys, extra safety pins, loose change, gemstones. In the seventies, some women, though certainly not Jima, even hid hashish to be smuggled through customs in a com

partment sewn into the bottom hem. Sometimes as she undressed and shook out her sari a secret bundle would strike me or Neela, just like those falling tamarind pods. We would try to stifle our giggles. We knew that, even though we couldn’t see it, she was exposed. At the time our only response to this advanced screening of womanhood was laughter.

In that room late at night, I’d also sometimes hear an urgent murmuring that I never quite understood to be what I know now it was: the quiet pleas of my grandfather, trying to get frisky in the dark. The forced proximity of our lives meant an intense physical closeness. When I was scared by a nightmare, I’d find my whimpering soothed by the arm of my grandfather reaching down to envelop me from his bed.

I was still a girl, unaware of the real meanings and intimacies of adulthood. Yet I did know where the answers to many of those mysteries were kept: inside the Godrej. Godrej was the brand of armoire we and nearly everyone else had, and just as the word “Kleenex” stands in for tissue, “Godrej” came to refer to the armoire itself. Technically, the house had four Godrejs. Yet only one mattered: the one in my grandparents’ room. Narrow and made of heavy steel, it looked like a locker with two doors, one with a squeaky handle above a keyhole and the other with a long mirror. If we kids heard a jangling of keys or the creaking of a metal door, we’d all come running, hoping to get a glimpse inside. Occasionally I’d loiter near the Godrej, like a cat beneath the dinner table, waiting for my chance. From my sporadic peeks into its interior, I pieced together a map of its contents. I knew the shelves were lined with old newspaper. On those shelves were piles of my grandfather’s bush shirts, buttoned-down, four-pocketed garments in plaid, simple prints, and polished cotton. He had about fifty and wore about three. His Rolleiflex camera was there, along with the black-and-white photos he took with it. The Godrej also contained my grandmother’s wedding sari, an ornately brocaded blue-and-black Benares silk, heavy with gold-threaded embroidery at the hem. My favorite of all her saris was a florid Technicolor blue-and-purple double-shaded thick silk with gold embroidery threaded throughout the body as well as the border.

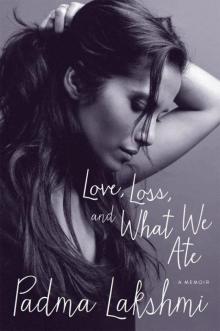

Love, Loss, and What We Ate

Love, Loss, and What We Ate