- Home

- Padma Lakshmi

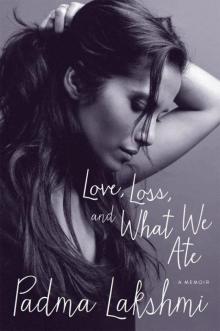

Love, Loss, and What We Ate

Love, Loss, and What We Ate Read online

dedication

For TJF

The heart knows no pain sharper than love’s arrow.

contents

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3 Kumquat and Ginger Chutney

Chapter 4 Yogurt Rice

Chaatpati Chutney

Chapter 5 Chili Cheese Toast

Cranberry Drano

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13 Egg in a Hole

Chapter 14 Kichidi

Chapter 15

Chapter 16 Krishna’s Pickled Peppers

Applesauce for Teddy

Chapter 17

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

chapter 1

It was the end of summer and the end of a life as I had lived it. The year was 2007. Inside the Surrey Hotel, which I would come to call the “Sorry Hotel,” then a musty residential place (much like the Chelsea Hotel, but without the artists), I sat on the floor with cardboard boxes towering all around me. These walls and floors cloaked in dusty beige and brown, with a linoleum- and Formica-laden kitchenette, would be my refuge—a place where the displaced, like me, put themselves.

One month earlier, I had finished moving out of my beautiful home: taking the last pictures off the walls, wrapping the last trinkets in tissue, and finally, nauseatingly, separating the wedding photos into two neat piles. Everything I had been carting from one stage of my life to another, to remind me of me, was in the boxes that surrounded me. And there were so many of them now, just days before my thirty-seventh birthday. But so little left of me. At the end of a marriage, no one wins. There is only anger, sorrow, guilt, emptiness, and defeat. Outside, it rained. There had been many rainy nights that summer.

I had been sitting, staring at nothing, for so long that my tailbone had started to throb. Far off, the muffled sound of a phone ringing and ringing finally penetrated my daze. As I rose to silence the phone, shifting my weight, I felt the sharp, sudden pull of surgical stitches on my abdomen. I reached out to steady myself against a box. As I did, it shifted. I heard the silky, scratchy rustle of cellophane against cardboard. Down tumbled dozens of dusty kumquats, from a bag that had been perched precariously on top of the stack. They were a gift from my worried mother, shipped from her garden in Los Angeles. When the avalanche stopped, my gaze focused on the bright, beautiful fruit, the orbs glowing orange against the dull backdrop of everything else. The man I had left was like that: he could illuminate any room, no matter how dim.

My future husband and I had met eight years earlier, in 1999, in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty. After my European modeling career had more or less come to a close in the late nineties, I embarked on a professional acting career in Italy. Starting in 1997, I also began to cohost an Italian television show called Domenica In. I was surprisingly busy with work, and after acting in two period miniseries in 1998, decided to build on what I hoped was a burgeoning career by moving back to L.A., where I had lived as a teenager. I came to New York frequently, too, as most of my friends and extended family lived there. I was finding my way again in the U.S. after spending most of my twenties in Europe. For the first time since college I was single. I dated some, but not seriously. Instead, I focused on auditions and on writing and then on promoting my first cookbook, Easy Exotic: A Model’s Low-Fat Recipes from Around the World.

For my first role, I had to gain twenty pounds, which was a cinch and a pleasure. Best three months of my life. Losing the weight after filming ended, not so much. I wanted to do it in a healthy way. The regimen I came up with was not quite a diet. There was no deprivation involved, mainly because deprivation is miserable: the more brutal or austere the diet, the harder it is to keep. Instead, I tweaked recipes for my favorite foods from around the world in an attempt to excise calories but not flavor. And those recipes became Easy Exotic. I landed a publishing contract for the book largely because, well, everyone wants to know what a model eats.

Tina Brown, ex–Vanity Fair and New Yorker editor, had recently founded a new magazine, Talk, as well as a publishing imprint, Talk Books, in conjunction with Miramax Books. My book, left over from the previous Miramax list, was one of her first books. I doubt my silly little cookbook, closer to pamphlet than proper volume, was her first choice. But somehow, I was invited to the new magazine and book imprint’s launch party, a Great Gatsbian affair on Liberty Island. It is still the best party I have ever been to, except of course for my own wedding, five years later.

On a balmy, beautiful August night, I came with a few friends, including my book editor (who would eventually become one of my bridesmaids). We all boarded the ferry and arrived at a fete lit by candles. Tina had invited such a strange and wonderful mix of people, a combination of the high-minded and the pop—a particularly glamorous herd of heads of state, cultural taste makers, movie stars, artists, models, writers, and other starstruck dilettantes like myself. After all, this was the woman who as editor in chief of The New Yorker had devoted (to jeers as well as to applause) an entire issue to fashion, starring writers like John Updike. She employed similar juxtapositions on the pages of Vanity Fair, too, and it had served both the magazine and her reputation well. It was what Tina was very good at. She brought really interesting people from the far ends of the cultural spectrum together. She enjoyed it. And she had the power to do it. It is a very important lesson in good hosting and curating that I still use today. This time, that room just happened to be all of Liberty Island. I found myself in an electric-turquoise Calypso slip dress (so nineties), laughing and dancing with the likes of Henry Kissinger, Todd Solondz, and Madonna, excited about my first book and my new life back in America. Colorful fireworks lit the sky.

There was certainly magic at work that night. Typically, parties are the perfect setting for the spectator sport that is people-watching. But, whether intentionally or not, this party was so dimly lit that you couldn’t quite see who the other guests were. There were low-wattage fairy lights strung about, powered by generators, but that was it. If you wanted to really experience the party and its luminaries, you had to dive in and walk around, get up close and personal. I found myself passing a very fair-skinned Indian man who looked familiar. We both turned somehow just in time as our eyes met. As we talked, I developed a hunch that this twinkly-eyed man with his arched eyebrows, salt-and-pepper beard, bald pate, and sharp nose might be Salman Rushdie. I was a teenager when the trouble had started, but even then I’d seen the images—I imagine most Indians had—of the man, our own Hemingway, whose life was under threat for his book The Satanic Verses and its supposed affront to Islam. His eminence was compounded by the controversy. But this man couldn’t be him. He seemed to know all about me. He asked me about my life in Italy, my childhood in Madras. I decided he was probably some distant uncle.

At some point, he gave me what even a naïf like me recognized as a pickup line. “I’ve always been interested in Indian diaspora stories,” he said, or something like that. “Perhaps we could talk about yours.” I was game, I told him. We exchanged numbers. “Can you write your full name?” I asked, which must have seemed odd, but he said nothing and did. Aha! I thought, as I read the scrawl. It is him. I wasn’t thinking very clearly but at least I’d have his autograph. This is how removed from my life this man was.

The next morning, I was in NoLIta, contemplating a Tracy Feith mustard-yellow scarf dress, when I got a call from a man with an Anglo-Indian accent. “Sorry, w

rong number,” the man said, and hung up. How strange, I thought as I bent over with the dress still half over my head in the tiny fitting room. I called back the number that now appeared on my nifty new cellular telephone. “Salman, is that you? Are you crank calling me?”

“Um, well yes, I think I just dialed the wrong number. But it didn’t sound like you. Uh, what are you doing?” he asked, uncharacteristically fumbling for words.

“Trying on a dress. I think I like it.”

“You should buy it,” he said.

And I did.

So our telephonic relationship began. At first, I thought it strange that someone as important and, I assumed, busy as he must be had time to talk as often as we did. Little did I know that writers are incredibly gifted at finding ways not to write. I soon solved the mystery of how he’d known about my life. Several months prior, in the course of promoting his latest novel, he had been featured in the Italian magazine Panorama. Inside, there was a small profile of me—he’d read it and saved it.

I had just gotten my first American cell phone a month before we met and the novelty of being able to take him with me anywhere—the Santa Monica Pier or the farmers’ market in West Hollywood—brought an intimacy to our calls. And a thrill, too. I described the world to him as I experienced it. I felt like a Bond girl with that phone pressed to my ear and that charming Anglo accent on the line. Years later I would see the film Her, by Spike Jonze, and identify with the main character’s mounting feelings about a computer OS that he becomes emotionally attached to. What would my friends think of me, having this telephonic relationship with a married author almost a quarter of a century older than me and living in England with Special Branch security protection? The whole thing seemed surreal.

It’s hard to explain now, but I fell in love with Salman over the phone. I was still in my twenties, and no one of his artistic or intellectual caliber had ever so much as crossed my path. He had such a mellifluous voice. Calm and mysterious, it gained an impish lilt just when he was telling you some juicy punch line. He had a wicked sense of humor and he seduced with his greatest weapon, his words. He knew how to construct the perfect compliments, too, layered with acute observations about me that seemed unimaginable coming from someone who’d been in my actual presence for mere minutes. He told me stories of his own childhood in Bombay, his early years in London. He confided in me and seemed interested in the most mundane and microscopic details of my new, lonely life in Los Angeles. He listened to stories of my childhood. He understood what it was like to be Indian in the West. He understood the awkwardness and melancholy of going back home, too. For the next three weeks we spoke two to three times daily.

In the soul-sucking intellectual desert that L.A. was for me at the time, I was starving for that kind of connection, and my future husband’s phone calls were a nine-course meal airlifted in with iced champagne to boot. His attention, almost more than his charm, seduced me. Despite my small-potatoes cookbook deal and the occasional invite to a glitzy party, I was not exactly flying high in L.A. I had left a life of glamour and a dram of success as a model and, more recently, as an actress in Italy to return to the city of my adolescence. As a foreigner, I felt there was an implied limit to my career in Italy, where I would always be a curiosity. I wanted to try my hand in America before it was too late. I wanted to make the transition to more stimulating work before modeling decided it had had enough of me. Worse still, I was turning thirty in a little over a year, a milestone that in the business of appearance might as well be a gravestone.

That was the backdrop when he started calling. During a time when no one seemed interested in me in Los Angeles, a man came along who was, and not just any man. Once, he called as I stood at the sink eating a peach, the juice streaking down my arm. I picked up.

“Hi, Salman,” I said. “Hold on for a second, I’m eating a peach.”

“What color is it?” he asked.

Could I really be so inconsequential if Salman Rushdie wanted to know the color of my peach? It sounds silly in retrospect, but at the time, in the midst of a crisis of self-worth, I eagerly took up the fantastical notion that I had begun to inspire this great man.

Salman lived in London at the time, but he rented a place on Long Island every summer. He liked being in New York, where even during the fatwa he felt safe enough to enjoy the city without his typical security detail. After a few weeks, I was set to come to New York to make my first appearance on the Food Network to promote Easy Exotic. He told me he was soon returning to the city for work and asked if I’d like to have lunch. He said he was married sometime in the first week by saying he was here in the States with his “family.” Nothing more. I knew damn well what he meant even though he had said it in the blandest way possible, but I didn’t stop speaking to him, because I was incapable of giving up this new exhilarating presence in my life. Up to that point our connection had been only verbal, only telephonic. So it was easy to justify how I could keep speaking to him. Nonetheless, I didn’t want to be that woman. I convinced myself that ours was a platonic relationship. Since no hanky-panky had gone on, I could continue my friendship with this man. I was powerless to refuse any contact from him whatsoever.

“I can’t go with you to lunch,” I said.

“It’s just lunch.”

Touché.

I proposed a stroll instead. It seemed simpler, more innocent, less fraught with potential for misunderstanding, less like a date. A walk, a stroll, could end at any time for any reason I could conjure up if needed. We were to meet at four o’clock in the afternoon on the steps of the Metropolitan Museum. He sat there waiting as I got out of the yellow cab, in my mustard-yellow dress. He wore his slightly rumpled look: a faded black T-shirt, baggy slacks, and a loose blue cotton jacket. We walked in Central Park, around and around the lake. The weather was perfectly sunny and pleasant. It was one of those rare late-summer afternoons when it’s warm but not too hot. Sunlight streamed through swaying maple leaves. Families were trying to squeeze out the last drop of summer, picnicking on the grass. Teenagers were playing Frisbee. We heard snatches of music from street performers as we circled the lake, smelled the occasional whiff of pot smoke. We enjoyed Mister Softee cones and lingered until the lake glowed, until the sun sank behind the trees. I cannot remember what we talked about except that we never stopped talking. I suppose we spoke of everything and nothing, just happy to be speaking now while standing, finally, on the same ground together. I lost track of time but knew some hours had passed.

He was staying nearby at the Mark Hotel. I said I’d walk him there. Because neither of us wanted the day to end, we had a drink at the hotel bar. In an attempt to be cool, I ordered a single-malt Scotch on the rocks. I was so nervous that I drained my glass. I had dinner plans with friends nearby, so he walked me to the restaurant. Not thinking what it might imply, I invited him to come along and sit down with us. I just couldn’t bear to say good-bye to him.

We fell into bed that night. At 3:00 a.m., I woke with a start. I’m naked in a married man’s bed. I got dressed and skulked out of the Mark, feeling like a hussy. Once home, I showered, attempting to scrub away my shame. There were so many reasons we shouldn’t be together. He was married, for one, with a young son. He lived in London. The ominous cloud of the fatwa hung over his head. He was twenty-three years my senior, old enough to be my father. I consoled myself by resolving that there was only one decision to make; the next step was too obvious to doubt. We would stop speaking. I would go back to my life and he to his. But he kept calling. And I kept answering. I could not resist him.

Speaking to his disembodied voice allowed me to convince myself that we were still two innocents. Our courtship already felt like a dream. His face had lit up television screens in India and around the world. Even before the trouble with Iran, he was considered a formidable writer and a great intellectual mind. Up close I had known only the weighty world of lingerie modeling. His gravitas was the spark that lit my attraction. He was ever

ything I wasn’t. He was a lot of what I wanted to be. He did not try to fit in. I had spent my career trying to be what other people wanted me to be, to embody whatever quality they felt was needed to sell jeans or bras or perfume. He had made a life of being different. I was totally taken by this man, and my admiration for him propelled me ever toward him. The fire burned because of his wit and charm and the connection between us. I had to admit, if only to myself, that this was not innocent, that now I had no platonic alibi to hide behind.

In him I had found a fellow wanderer, someone who knew what it was to always feel slightly displaced. In my case, I had spent years shuttling between India and the U.S., then later throughout Europe. He, too, was an Indian raised in the West. He understood my experience firsthand.

In L.A., I spent much of my time milling around commercial sets with teenagers. Many models don’t finish high school. The girls were sweet, the conversation less than stimulating. I was intellectually curious and I wanted to be stimulated and challenged. I loved books. The important mentors in my life had valued learning. There was Mr. Henniger, my high school English teacher and Academic Olympiad coach, who threw end-of-the-year parties where you had to come dressed as a literary character. He came as Godot, a sign on his chest reading, “I’m here!” There was Michael Spingler, a French professor from my college and later, when I was a starving model in Paris, a savior who invited me into his home to share pots of beans and lardons with his friends—bookstore owners, poets, and authors. There was my grandfather, a hydro-engineer who retired only to get a law degree and become a practicing attorney, only to retire once more to become a tutor to college students studying math and science as well as the humanities. I was primed to value what Salman had to offer of himself, and it fed me so completely that I was blinded to everything else.

Love, Loss, and What We Ate

Love, Loss, and What We Ate