- Home

- Padma Lakshmi

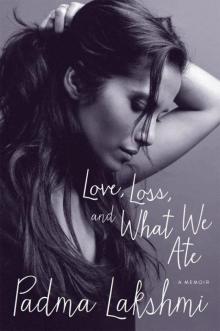

Love, Loss, and What We Ate Page 30

Love, Loss, and What We Ate Read online

Page 30

During the surgery, I waited upstairs near his room with his sons for the doctor to call us down. I remember lying on a leather couch and dozing there long enough for my cheek to stick to the cushion. Two hours or so later, Margot, a woman from Teddy’s office who was also waiting with the boys and me, came from the nurses’ station and said Dr. Gutin had come out of surgery, and while they weren’t finished with Teddy, he wanted to speak with us.

Dr. Gutin came into the small private room where we waited. It had pale-gray walls, wall-to-wall carpeting, and puce-colored faux leather and wood sofas. It was as bland and nondescript a room as possible, designed not to make any kind of impression on its occupants while they received potentially devastating news that would forever change their lives. There were four chairs facing each other, two on the left and two on the right. A couch was beyond them against the wall. Margot and Siya sat across from Everest and me. When he came in, the doctor still had on his OR scrubs and looked a bit sweaty and tired. He said that they had found the worst. The tumor had crossed the brain barrier to both lobes, and it was the deadliest of possibilities: glioblastoma. When I asked the doctor what that meant, he said “six to nine months or a year to live, maybe more if he has treatment; a year and a half if he’s really lucky. But he must start treatment right away or he will be dead within six months.”

It felt as if someone had inserted an electric rod into my side, and I wailed, an agonized, loud cry, like a wounded animal, a dog hit by a speeding car. I collapsed, weeping, into Everest’s arms. I felt as if I were choking. I curled deeper into myself as my tears and snot stained his sleeve. My chest became concave with the sudden and sharp pain my body could not thwart. For everyone in the room, but especially for the boys, the moment was intense and agonizing. Love and respect dictate that I not speak to how Everest and Siya reacted to learning their father’s fate, as it is not my story to tell for them. Such a private moment belongs to them alone.

Teddy had come back from Africa shortly before Krishna’s birth not with spinal meningitis, but with this tumor. It had grown and developed just as the baby had. While Krishna learned to crawl on Teddy’s plane, while she pulled herself up to stand and took her first steps, the tumor, too, had grown and taken root. While the baby grew each day, so did this invasion in his brain; this malignancy; this killer of joy, hope, of memory; this parasite.

I looked down at my watch, a simple Jaeger-LeCoultre Teddy had given me, a smaller replica of the one he wore. I saw it was 12:30 p.m. I had a meeting across Central Park, one of my very first with the overpriced court-appointed forensic specialist, Dr. Pizarro, whose job was to determine if I was psychologically fit to retain custody of my child and to report back to the court. As I walked to the elevator, I listened to a voice mail from Teddy I’d saved about the law suit after we flew back from the Bahamas. “Now, Junior, things are gonna get hard. You’re going to have to keep calm, keep your head straight. You’re smart, so be smart now. Don’t get scared. This is real life. I will always be here, of course, but I can’t always hold your hand. So prepare yourself.” How was I going to prepare for what lay ahead? I could not even fathom what the future would look like.

Outside, on York Avenue, the trees were in bloom with tiny white flowers. Petals blew in the breeze like confetti. Thirty years earlier, I had routinely roller-skated to this very spot to meet my mother for her lunch break. We would buy two falafels, dripping with tahini and hot sauce, and eat together before she went back to her nursing shift. I thought of how Teddy would react to eating a falafel. “Ooof, sounds like a bellyache in a bag,” he’d probably say. I hailed a cab and pushed my body inside. We headed across town. My mouth pronounced the address on the Upper West Side to the driver. The sound of my own voice was jarring to hear.

On my way to the psychiatric evaluation, I sat and blinked, motionless in the taxi. In one swift day, life as I knew it had changed. Again. What was waiting for me on the other side of the park would also have a great impact, on me and on Krishna, the only other person in my life as important as Teddy. I looked out the cab window and saw the sun come through the trees, light and shade dappling my face. We wended our way through spring in Central Park. The atmosphere was thick and I heard myself breathe. I could smell cut grass and cherry blossoms coming from the half-open car window. It was as if I had been dropped into some movie version of a life not mine, a melodrama that I, as a character, now had to assume was mine and resolve, a maze to which I did not know the end.

I knew that I had to get a hold of myself and put the life-altering information I had just received into the very back of my head until my meeting with Dr. Pizarro was over. I was advised by my attorneys not to cancel any appointments because it was important to be as reliable as possible. This one had been scheduled before Teddy’s surgery and I just wanted to get on with it, get it out of the way. It would be better to do the interview when I was still in shock and on autopilot, before I had time to truly process what it all meant. The stakes were as serious as they could possibly be, so I had no choice but to put one foot in front of the other and walk into that office.

Dr. Pizarro was a very tall and broad-shouldered man. He had the same build and large body type as Adam, and he inspired the same uneasiness in me. I did not want to disrespect Teddy’s privacy and so I withheld the gravity of the situation I had just come from. I told Pizarro that someone close to me had had surgery, to give context to any behavior of mine that seemed distracted or strange. I could not judge my words or movements accurately. My spirit went limp as I reentered my body, and I submitted myself to this man’s questions, trying not to appear uninterested or dead inside. I answered him as concisely as I could. I asked if I could take notes, too, which I did in a small black Moleskine notebook I produced from my handbag. I tried to write down a few words that would jog my memory later when I recounted what had happened in the interview to my lawyers.

I felt like I was answering a compulsory questionnaire before I went to prison or my own execution. I had no choice but to be there. I didn’t know if I could go up against the might of the Dell lawyers, and I could not go to Teddy for help. I didn’t know how to process the information I’d just received from Dr. Gutin. I couldn’t think. I did not have time to form any of my own opinions. I could only be present. I focused on what really mattered, Teddy and Krishna, and it somehow got me through the day.

In one instant, Dr. Gutin’s news had given me great clarity. That was the terrible blessing again. I wanted to savor the love we had among the three of us; I wanted Teddy to feel as loved as possible every day he had left. I wanted Krishna to be shielded from the very real danger I constantly felt.

I didn’t know what my life would look like or how much time I was going to have with the two people I loved most in the world. But I knew that if I could just get through this meeting, I could heave myself back into a taxi and go downtown, go home to nurse the baby in my arms, go home to grieve in private, go home to prepare for the worst.

chapter 16

By May, Teddy was well into chemo and radiation. I remember escorting him into the room where they keep the large cylindrical radiation machine. I had been in this very room thirty years ago when my mother had taken me to work one day. Unbelievably, the room had not changed at all in that time. I had the sense that I had stepped into the past, and I wished fervently for the power of time travel, to return to a time before Teddy was in pain, when the grim reality of this moment had been unthinkable. I would’ve given anything just to be able to slow down time at least a little. But of course I couldn’t. So when I first received the schedule for the next season of Top Chef—filming would resume at the end of June and go through early August—I thought seriously of bowing out. Teddy did not want me to stop working. I felt tremendously conflicted, but Teddy insisted.

I flew home twice during filming that summer, and each time Teddy seemed thinner and thinner. We spent the remainder of August shuttling back and forth between his beach house in the Hampton

s, where we spent the weekends, and the city, where during the week he had chemo and radiation at Sloan Kettering.

We were all happier and less stressed at the beach. Teddy played well with Krishna, and she relished his attention. She made him laugh to no end, and they seemed to have their own language and private conversations. Teddy had always been more physical with the baby than I was, and she did not understand why her poppy was now so standoffish. She was much more verbal by this time and would try to pull Teddy physically toward the swimming pool.

Just a summer before, he had spent most weekends teaching her how to float and swim, supporting her little body with one open hand. She would also sit upright on the couch next to him in the TV room, amused during golf or tennis matches, cooing and smiling at his commentary. “Aw jeez, would you getta loada that swing, for crying out loud,” he’d complain to his pint-sized sidekick while she shook her sippy cup in agreement. This was the only time Krishna got to watch TV, and she was mesmerized by any person swinging any blunt object at some ball or other on the screen. “You’d never choke like that, right, kiddo? No can doosky!” I would pop my head in every now and then from the kitchen to see what they were up to, and they were as content as two peas in a pod.

This summer, however, Krishna was not only more verbal but also very mobile, and she was getting heavier. She would climb all over Teddy until one of his sons would come and lift her off him. She tugged at her poppy’s sleeve, begging him to take her out. When he said he couldn’t, she climbed onto the couch and went directly for his head. She gently stroked the ropy, livid J-shaped scar on the side of his scalp. “You boo-boo? Is okay, is okay, Poppy better,” she soothed, mimicking the voice I would use when she fell, bumping her elbow or scraping her knee. Those last days of summer, not only did Krishna have growth spurts but her language skills, too, developed rapidly. It felt to me that with every leap forward I sensed in her, Teddy took a turn for the worse.

On one of my trips home during filming, Teddy had become extremely dehydrated and I drove him to the Southampton hospital, where we met a tall and sturdy nurse named Sarah in the ER. I asked her if she ever did private duty and she said yes. The advent of Sarah in our daily lives at the beach was both a blessing and the curse of the inevitable. Krishna was at first scared of this big woman dressed in white who seemed to always want to prick her poppy with needles and tubes. But eventually, Krishna got familiar with Sarah, and the IV pole, too, helping to push it alongside her poppy as he struggled to stay on his feet long enough to get from couch to dining room. It frightened me to see Teddy’s physical strength ebb away from him. He had always been a solid and strong presence, virile and active, even when compared with men younger than him, whose hair was nowhere as thick as the shock of white he trimmed twice every month. His posture began to suffer and we all struggled to get him to eat enough.

We were losing him.

Watching Siya or Everest help Teddy walk, Krishna wanted to help, too. This ragtag procession broke my heart but was at times also comical as we tried both to keep Krishna out of the way and to let her feel a part of all the activity. Everest was the preferred choice for Teddy to lean on, and so Siya and I usually trailed slightly behind, steadying the IV pole and hoping neither Teddy nor Krishna would trip or fall over each other.

One early evening, I looked outside at the tall, reedy grass growing between the house and the ocean. The sun was setting. The already tan stalks glowed golden in the last light of the day, and I could hear the sea over the television. The tall shrubs swayed and rubbed against one another, rustling in the sea wind. The wet aroma of tomatoes simmering in the kitchen hung in the air like a warm cloak. Maggie, Teddy’s cook, was stewing up a cauldron of the last of the late-summer tomatoes. My stomach grumbled. Now and then I could hear a yelp or a whoop from the front of the house, where Everest and Siya were playing tennis. The baby played at our feet with some blocks.

Teddy said he had just been remembering a dinner we had attended together, but that the memory didn’t make sense. He didn’t know why. He didn’t know what he was saying exactly, but he knew enough to know that his brain was playing tricks on him. It worried him. He thought that what he remembered happening hadn’t happened. He was right. The memory was a jumble of memories conflated into one. He had overlapped separate events and did not know how to untangle them. He didn’t know what was true and what was his mind short-circuiting. He said there had been a dinner or a big banquet, and it looked like I was shooting Top Chef, but he was there, too. And for some reason the chef Daniel Boulud was with us.

All three things he remembered were a plausible combination. Teddy did throw a big charity dinner around that time every year called Huggy Bear. But this was not a Huggy Bear dinner, he said. And he knew Daniel well, too. Teddy dined often at Café Boulud, which was coincidentally in the lobby of the Surrey Hotel, for years with his mother and then with me. We dined at the restaurant Daniel on special occasions, too. I had arranged his seventieth-birthday dinner there, a week before Krishna was born. Teddy loved the steak and when he got too sick to eat out, Daniel sweetly sent rib eye and potatoes home to the Manhattan apartment with the driver. Teddy had also visited me on the set many times, but never for a big event or banquet. He knew all this, but he still had trouble sorting through what was real and what was imagined. The confusion. He could not tell the subtle but important difference between possibility and actual memory. That was the first time he noticed being confused. It scared us both. Losing his mental faculties was his worst nightmare.

I felt the evening chill creep into me and reached for a nearby blanket. “Summer is almost over,” I said, trying to change the subject. “So am I,” his eyes seemed to be saying back.

Sometime after my forty-first birthday on September 1, back in the city, I was still trying to jump-start Teddy’s appetite. I wrapped Krishna up into my Baby Bjorn (although she was getting heavy by this time) and went to the farmers’ market in Union Square hunting for goodies. A trip to the Greenmarket always gave me a sense of well-being and elevated my mood. It was a favorite outing for Krishna, too. She loved all the hustle and bustle of the vendors and the motley crowd that passed through; the dreadlocked skateboarders whizzing by; the flowers she stuck her nose right into on days we went with the stroller; and the piles and piles of fruits, vegetables, cheeses, and breads and other baked treats heaped in every stall. It was my favorite time of year, the hinge moment between seasons, between the full bloom of summer and the chill of fall creeping in slowly.

Krishna enjoyed touching and fingering all the different-colored vegetables like spiky, spiraled neon-green Romanesco; yellow and purple corn, with their soft silk sprouting at the top; nubby sweet potatoes; fuzzy peaches; and juicy plums. She ate blueberries by the handful, and loved the crisp bite of sliced Asian pear. And she was a good sport about trying every strange nugget of cheese that was offered. All the vendors were more than generous with their samples, waving them in front of her nose. She dangled from my torso facing outward, eager to taste the world she had yet to discover. The market was exhilarating, a bountiful place to exercise her senses.

The chemo made Teddy quite debilitated and nauseous, and the thrush that came with it coated his taste buds like a blanket of snow covering spring grass. Even the Marinol pills did little to restore his interest in food. Teddy’s appetite had been decreasing by the day, and I could think of nothing as nourishing as a white ragu made with veal and mushrooms that he loved. He had eaten a similar version almost weekly across the street from his office at Cipriani, in the Sherry-Netherland hotel. I found some lovely hen-of-the-woods mushrooms, and some trumpets, too. I bought fresh dill and other tender herbs from my favorite stall, which also had at this time what I considered to be the jewels of the farmers’ market: chili peppers.

Hot, and hotter, and hottest chili peppers, in bright red, dark green, marigold yellow, and purple-black as well as a fluorescent orange. All spring and well into the end of summer, this stall was o

ne of the biggest in the market, consisting of a horseshoe of three tables with lanes of tables in the middle. Behind the back wall of tables, hanging from the tent covering, was a chart listing the different kinds of peppers and their supposed numerical rating on the Scoville scale. This stall, laden with these riches, was what I looked forward to most. I disregarded the famous measurer of capsaicin (the substance that provides spicy heat) in each of the peppers and preferred to sample them on my own, usually with a bit of bread and cheese in hand to quell the sting between bites. I bought a handful of Scotch bonnets, about a cup of green and red small Thai chilies for cooking, and a heavy cellophane bag of round red cherry peppers the size of Ping-Pong balls. I always bought a random sampling of ones I was curious about, mostly for their physical beauty. I made sure to get a decent-sized bag of mild chilies for Krishna’s sake. She could not resist getting in on the action. I had to fend off her arms, outstretched inside mine, trying to touch every colorful and dangerous little bomb as I bent forward. I usually made her hold the hunk of bread, and she would gnaw on it, soaking it with her saliva.

Love, Loss, and What We Ate

Love, Loss, and What We Ate