- Home

- Padma Lakshmi

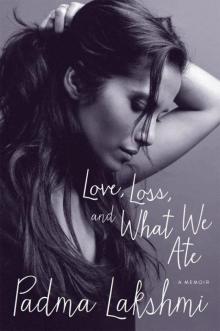

Love, Loss, and What We Ate Page 17

Love, Loss, and What We Ate Read online

Page 17

I accepted that I would get only so far with my aesthetic handicap. So I made an appointment to undergo chemical dermabrasion to take some of the dark pigment out of the scar. This wasn’t the first time I’d tried to reduce its visual impact. Before I had cold-called Nina Blanchard’s agency, I’d visited an Indian surgeon named Dr. Raj Kanodia in L.A. recommended to me by another model. He told me that while he couldn’t erase the scar, he could significantly flatten it, making it easier to hide with makeup. This might be uncomfortable, he said, before inserting a needle as long as an asparagus spear and withdrawing it excruciatingly slowly to ensure an even distribution of Kenalog. The injection did flatten the scar but left me terrorized. Now, after a year in Milan, my agency identified a doctor—agencies had Rolodexes filled with doctors who could fix anything from teeth to tits—who treated it inch by inch as I gritted my teeth and cried. This was primitive dermabrasion—essentially a controlled chemical burn, a painful stripping of layers of tissue—which I hope has improved since the early nineties. I had never known such agony, even during painful monthly periods and in the car accident itself. But the procedure worked. After a dozen sessions, about half an inch of the scar had been visibly pruned of a few layers of knobby tissue and was now a neutral color, close to that of the rest of my arm.

My agency sent me for a go-see with the agent Davide Manfredi, who was looking to cast the next photo series for a photographer named Helmut Newton. Art lovers, fashion-industry types, and Vogue-magazine devotees—they all knew Helmut Newton. I’d first heard of him when I was in college. In the same league as Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, he was a trailblazing photographer who made his own rules. Mr. Newton urged fashion photography from the restrained toward the provocative—a big deal at the time for a demure industry. (A Vogue editor reportedly admonished him: “Ladies, Helmut, do not lean against lampposts.”) He was perhaps best known at the time for the series Big Nudes, unflinching, elegant portraits of women who were completely nude but for a pair of high heels. Being chosen as his subject was a potentially career-making job.

When my turn with Davide came, I entered his office with familiar trepidation. He told me to strip to my underwear. I was neither surprised nor entirely comfortable. I had been modeling for a year and was more or less immune to the humiliation of being photographed in this state. It had become only mildly unpleasant, like getting blood drawn. At least by now I knew enough to shave first. As I undressed behind a partition, I gave him my requisite scar spiel, half expecting him to tell me to put my clothes back on. “Don’t worry, Helmut likes scars,” he said. He took a few Polaroids, affixed them to a piece of paper, and faxed them, along with hundreds of others, to Mr. Newton in Monte Carlo.

The audition came and went. I thought little about it, because I did not for a second expect to get it. I was a benchwarmer for my agency. Once in a while, when a job came in that wasn’t commercial, they called me in to take a swing. I had a better shot at scoring that kind of job, where the model would be a subject of art, rather than a consumer aspiration. While an ad exec would not see my “exotic” look as relatable, the artist might at least see it as fun to photograph.

My career so far had been an elaborate game of pretend. I was a model who barely got work, who existed on the lowest rung of the business, and who saw no indication of that changing. I was still effectively in debt to Luigi for the plane ticket to Milan and to City Models in Paris. Somewhere in me I understood that the farce would soon end and I would move back home, go to grad school, find a real job. As a result, I was only partly present during my auditions and shoots. As I stripped for Davide, I felt as if I were role-playing, as if I were looking through someone else’s eyes.

Two weeks later, I got a call from my agency. They informed me that Mr. Newton wanted to book me for a private commission. Me! Perhaps the coolest part: he loved my scar. The minute he saw it, Davide later told me, the great photographer said, “I have to photograph her.” My agent was thrilled, of course, almost shocked. Everyone at the agency seemed genuinely happy. The underdog had won one. I was an MFA student getting a story in The New Yorker.

This could be the job that launched me from an unknown model with a funny name to a model with a funny name that bookers recognized. Instead of being just one of three hundred models on a casting call, I’d be one of forty. If I was able to say I worked with Mr. Newton, it would no longer matter that I wasn’t the most beautiful or talented model in the business. Once you graduate from Harvard, does anyone really care about your GPA? Get through this, my agent promised, and I could forever sport his imprimatur. The subtext for me was that my scar, that indelible blot on my body, would be effectively erased.

Once the excitement faded, I began to confront what the shoot would entail. Mr. Newton, I learned, had been privately commissioned by a Japanese businessman to do a sort of Big Nudes redux. It was not to be published or exhibited but merely hung, perhaps in his dining room. I’d have to be naked. To get a sense of how naked, Daniele and I went to a bookstore to look at Mr. Newton’s work. As I flipped the pages, I understood that this was not “strategically placed fabric” naked. It was full-blown, oh-my-that’s-your-vagina naked. I was terrified of posing completely nude. I was a child of conservative India, where women went to the beach in their saris. My grandfather was still alive. He would not be happy. I also hated the idea of a photo of my poontang hanging in some banker’s dining room. This was an odd reaction, I now realize. But for some reason I’d rather have had thousands of people staring at my body than just that one.

Vag was the final frontier, the thing you still didn’t see on TV or in mainstream ads and media. Italian magazines like Max and others did show fully nude models, and many respected Italian actresses and TV personalities had gone full frontal by then, some more artistically than others. Later, I would do Max magazine, but that was still to come. At that moment in time, in 1993, just showing my boobs with both nipples blazing seemed like a crossing of some Rubicon in itself.

My body tensed as Daniele and I leafed the pages of one of the Newton books. Daniele noticed. “You should only do it if you’re comfortable,” he said. “If you’re not, it’ll show.” He was right. You can fake being bubbly for a Folgers shoot. You can fake the obligatory stoic look of the runway. But when you’re entirely exposed, the camera won’t be fooled. And I couldn’t go all the way to Monte Carlo on this legendary photographer’s dime to be a disappointment.

Yet whenever I thought I’d finally decided to demur, the infectious thrill among my colleagues and my agency pulled me back into “maybe” land. Perhaps I was just nervous. I didn’t want my fear to torpedo such a huge opportunity. I spoke to my mother, who has never been prudish. She had raised me not to be ashamed of my body, and to appreciate the female form and celebrate it. We both routinely went naked around the house when there weren’t others around, and I never saw my mom behave as if she were ashamed of her own body, no matter what. We even went to a nude beach once in San Diego, when I was an adolescent, mostly out of gleeful curiosity but also because my mom and I did like being naked. I mean that we just liked the naturalness of it. At Black’s Beach we quickly became bored after seeing that most of the other beachgoers were older gay men. Any shred of feeling risqué or sexy because we were nude on that beach quickly evaporated. My mother understood that posing nude could be a celebration of the female form, not just the culmination of male fantasy. Yet as the days crept forward, my doubt grew. Two days before the shoot, I got into my bed and called my agent. Exasperation barely concealed his fury. No one says no to Helmut Newton, he said. I had embarrassed the agency and myself.

A few weeks later, I got a surprising call from my modeling agent. Mr. Newton was shooting a calendar for Lavazza, the Italian coffee company, and wondering, what if I wasn’t completely nude, but just topless? Not only hadn’t I blown my moment, but I didn’t have to compromise in order to grab it. I was glad and relieved they still wanted to work with me, especially as I was still

feeling a bit like a chicken for turning the other job down, especially at the last minute. The atmosphere in Milan at that time in the early 1990s was much more liberal than in America. Italy (Catholicism notwithstanding) was much less puritanical than the United States, and overt images of female sensuality and sexuality were much more prevalent in magazines and on TV. Women with fully nude breasts nursing infants in commercials for baby bottles or formula were commonplace on Italian TV. It was also a time before the Internet. Things you did in photos couldn’t haunt you and follow you in the same way.

More than exploitive, the atmosphere seemed to be one that celebrated the female form and equated breasts with femininity and motherhood. Often all but the cracks of buttocks were exposed in thong bikinis, and on beaches along the Mediterranean and Adriatic Seas, grandmothers and teenagers and everyone in between bathed and sunbathed topless. Even excursions in Sardinia with Daniele’s family proved eye-opening. So the compromise, the willingness to show my breasts, seemed an easy one. I mean, if even Daniele’s mom could go topless then surely I could, to work with an artist like Helmut. I didn’t regret refusing the first job with him, but I was left with a feeling that I had missed a great opportunity, not only for my career, but also as an artistic experience. At that time, as now, pretty girls were a dime a dozen, and most of them didn’t have the extra handicap of being brown or having a scar seven inches long down their arm. Retouching was still not an option for almost all but Vogue covers back then. Models poured out from every residence and hotel. Milan was the first stop while building your portfolio, and if you didn’t want to do some job, there were lines down the block of starving girls who would, with a smile.

The other motivating factor was that this time the job was not for a private commission, but for a Lavazza calendar! Lavazza is one of the oldest companies in Italy. Like Pirelli, they commissioned great photographers to shoot an annual pictorial calendar. So I guess the coffee company didn’t require full bush! Not only would I not have to put my nether regions on display, but people would also actually see my work with Newton.

Daniele drove me to Monte Carlo. The shoot was in a suite at the Grand Hotel. When we arrived, I went upstairs, and Daniele sat on the hotel patio reading Corriere della Sera. I reached the suite only to find that one of my closest friends, Antonio Gazzola, had been booked as the makeup artist. His presence was a good omen. In those early days, he was somehow always there at the right moment. Backstage, he used to whisper to me in Italian that I was just as beautiful as all the other models and that my scar made me special. He knew how anxious I was about the scar and would tell stylists they didn’t have to worry about putting me in short sleeves, because he would make the scar disappear. Of course, they always put me in long sleeves anyway.

Now, though, he left the scar alone, because Mr. Newton didn’t mind it—or so I’d heard. Antonio was finishing up when Mr. Newton came in to say hello. He treated me gently and kindly, as a grandfather might. He spoke about his wife, a comfort to a girl about to spend an hour topless with a strange man in a hotel room. I began to feel at ease in my own skin. Then he caught a glimpse of my arm. “What have you done!” he gasped.

I began to panic. After the agony of turning down his first offer, the thrill of a second chance, and the years of wondering whether my scar was a deal-breaker—whether the accident had permanence—Mr. Newton’s reaction could be the ultimate rebuff, the moment at which my wondering whether I could make it as a model was met with a definitive “No, you cannot.”

“Didn’t they tell you about my scar?” The words barely escaped my mouth. “Yes, yes,” he said, “but why have you erased a part of it? You’ve ruined the beauty of it. Antonio, get your paints out and restore that mark to what it was.” I couldn’t believe it. I can still remember Antonio smiling with a brush between his teeth as he touched up the scar, adding wine-colored lipstick to the lightened areas. “Crazy business,” he murmured under his breath. While I was there, Mr. Newton booked me right away for another project. In these photos, my scar, not my boobs, was front and center. I felt so comfortable with this man, so safe. And when I posed for a picture for Big Nudes 2, you could see only the side of my face in the Polaroid he showed me. The scar was the star. The Lavazza calendar I wouldn’t see for ages yet, but he did send me a print of my own of the Big Nudes portrait.

Antonio knew what I didn’t: when the designers found out I had shot with Helmut Newton because of my scar, not in spite of it, they would all want to use me. Already grunge was in, and models with tattoos and piercings were showing up in American ads for Calvin Klein, and Europe often followed America’s lead. Helmut would give everyone in Milan and Paris the courage to use me without camouflaging my scar, Antonio said.

He was right. And it helped, I’m sure, that my agent milked the shoot for every drop—oh, did I mention that she just shot with Helmut? That he loved her? That he rebooked her on the spot? I was soon booked for an eighteen-page shoot for Italian Elle and I shot Roberto Cavalli’s first campaign with Aldo Fallai. I was booked for many shows in Paris, from Ungaro to Sonia Rykiel. At the shows stylists still checked my sleeves—but now they were checking to make sure the sleeves were short, so that everyone would know who I was under all that makeup.

Bigger jobs presented more opportunities to improve as a model. I learned how to walk from the legendary modeling agent Piero Piazzi. “You walk great,” he told me, before essentially advising me to change everything I was doing. I shouldn’t move my shoulders or my head. Just my hips. I had been overdoing it, walking the way my young daughter does today when she pretends to model. Gradually I got better at the strange craft of modeling. I learned to hold my body in a nonchalant way for editorials in that nineties grungy attitude that seemed to be screaming, “I don’t care if you take my picture.” I learned to move in a way that made the clothes swing and look fun on the runway. I also began to understand how to make my body seem slimmer and longer in lingerie and swimsuits on film. My growing success came in part from Mr. Newton’s photos, but also from my newfound confidence, which his embrace provided. All of a sudden, agents at castings were excited to see me. The spring in my step showed in my work.

For the next four years, I lived most of the clichés that come with modeling success. There I was partying on yachts, going to conspicuously cool restaurants, and heading to Ibiza for the weekend. I’d awake on a boat with Daniele, parked near just a few others in the Mediterranean Sea, and go to the prow wearing only my bikini bottom. I knew that men and women on the other boats might see me. And if I knew someone was watching, I might turn so my scar was visible. My scar became adornment, like a string of pearls. Almost overnight, it had transformed from a stain into a sort of talisman, a source of power and confidence.

Today, I love my scar. It is so much a part of me. I wouldn’t remove it even if a doctor could wave a magic wand and erase it from my arm. I’ve started seeing my body as a map of my life. I can tell a story about every imprint life has made on my skin: the mosquito bites on my back from when I slept under the Sardinian sun the summer I first fell in love with Daniele; the scrapes on my leg from the rocks in the Cuban sea during the filming of my first movie. In her introduction to Women, by Annie Leibovitz, Susan Sontag asks, “A photograph is not an opinion. Or is it?” I believe it most certainly is. A photograph can change the way you look at yourself, though it’s more complicated than that. Perhaps it was under the right light, or through the right lens, that I really saw myself for the first time. I have Helmut Newton to thank for that. People have told me that my scar makes me seem more approachable, more vulnerable. Ironically, the greatest gift fashion has given me is the courage to expose that most vulnerable part of myself. By facing the shame of my own body’s disfigurement, I was able to liberate myself from that shame, and instead draw confidence from my scar.

chapter 8

I never decided to stop modeling. By 1997 or so, I was getting bored and less and less ambitious. I would work only if I nee

ded the money, but I had no healthy desire to really make as much money as I could. And it’s hard to get anywhere with modeling if your look goes out of favor with fashion and its trends. I was not a waif. I once got fired from a Sonia Rykiel show because I gained too much weight between seasons. I was bored and it seemed modeling was bored with me, too.

Fortunately, another career began to take shape. Because I was a foreigner who spoke Italian—a relative novelty—I was a sound bite favorite of the news crews that covered the fashion shows for the style-conscious Italian media. Eventually, RAI television asked me to join the cast of Domenica In, Italy’s version of the Today show. I asked the director about showing my scar on TV. “Everyone knows that you have a scar,” he said. “Don’t cover it up.” I spent every Sunday for six months on live Italian TV in Rome and lived the rest of the week in Milan. The show provided a sort of training ground for every TV job I’ve done since. Each live show lasted six hours, and it aired without even a five-second delay. The anxiety this induced motivated me. I could finally make use of my mind. Sure, I was more Vanna White than Katie Couric, but at least I finally had a job where the goal wasn’t to shut up and look pretty. Plus, these were those heady pre-Internet days when a slipup wouldn’t make it around the world in a matter of hours. No one from back home would even watch the show.

The producers played up my role as the screwball-comedienne foreigner still learning the language. I had my own segment on the show called Parole a Parole (Word for Word): I had to attempt to provide the definition of a difficult Italian word and an elementary school student would get to guess whether I was right or wrong. In my dressing room, I had hundreds of letters from kids vying for the honor. The producers loved that sometimes my Italian would fail me. By then, I could speak the language rapidly and intelligibly. I just happened to speak a strange pidgin dialect that was part cab driver—my unofficial teachers—and part profane fashionista, thanks to Daniele and his friends. This occasionally made for exciting television. When one of the show’s other hosts teased me on air, I teased back, attempting a gentle insult like “jerk” but accidentally using the word stronso, which essentially means “piece of shit.” The slipup earned me a clip on Blob, the Italian version of Talk Soup, a show so popular it spawned a verb—blobato, as in “Mi hanno blobato!” (“They blobbed me!”).

Love, Loss, and What We Ate

Love, Loss, and What We Ate